In a piece which seems to have been written at a dangerous point some years before Horace launched his first three books of odes in 23 BCE, he turns for help to the Goddess Fortuna, while recognising that the fortunes that she has in store for Rome after a long period of civil wars could be bad as well as good. This ode seems as deeply and personally felt as any that Horace wrote, and is surely no mere literary exercise.

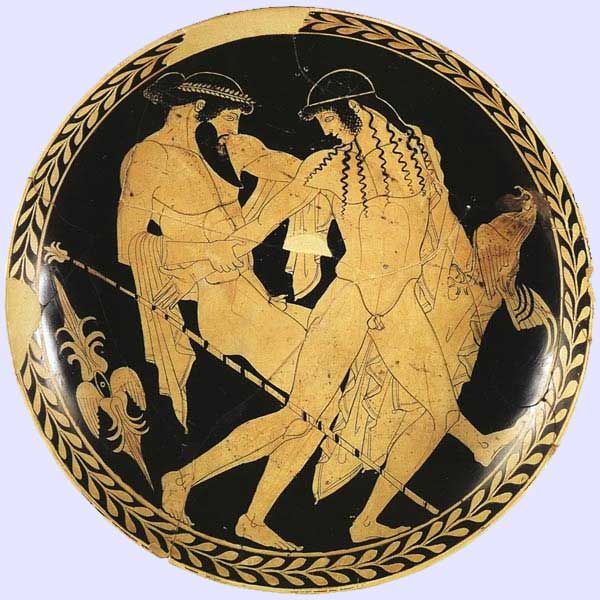

In the illustration, from a mediaeval manuscript of the Carmina Burana, Fortuna governs the cycle of life.

Hear Horace’s Latin and follow in English here.